All performers have the goal of reaching their potential and performing to the best of their abilities. A lot of time and effort is spent learning the physical techniques and skills that are required for sport. While the physical part of sport is highly important, peak performance can’t take place without a strong mental base.

Just as physical and mental performance go hand-in-hand, so do mental performance and mental health. One in four people struggle with their mental health; four out of four people have mental health. Having strong mental wellness is required to reach peak performance on the playing field. Our team at Premier Sport Psychology often explains this relationship to athletes by using the wellness continuum.

The Wellness Continuum- What is it?

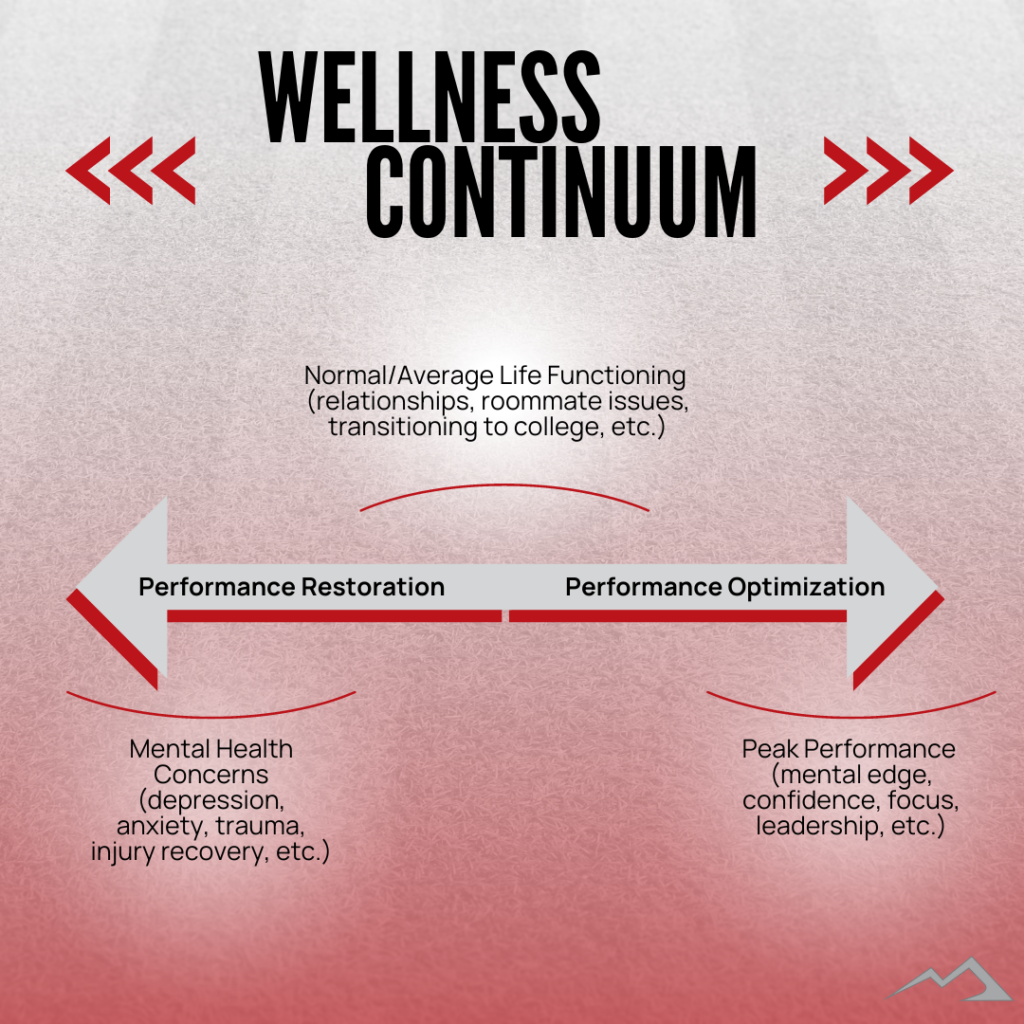

There are two ends of the spectrum on the Wellness Continuum; on the left is performance restoration, which refers to mental health struggles or concerns. On the right is performance optimization, which is your athletic performance. To achieve performance optimization you must capitalize on your performance restoration. Mental health is the base that is needed to move further right on the continuum. In other words, developing a strong foundation in mental restoration opens the door for strong mental performance.

Let’s break it down…

Performance Restoration

The far left side of the wellness continuum deals with mental health concerns. Regardless of whether you have a mental health diagnosis, all athletes and humans experience times where their mental health is not as strong as they’d like it to be. Things that cause your mental health to suffer such as burnout, anxiety, depression, or injury recovery all fall on this side of the continuum.

“If our mindset is in the restoration phase, there is likely something we need to address first before moving into mental performance skills,” Premier’s Dr. Adam Gallenberg says. “These could be things like chronic stress and underlying anxiety.”

Gallenberg likens the scenario to how an athlete would treat recovery from an injury.

“It is comparable to an injury. Before we can work on mental performance skills like focus or imagery, the injury needs to be addressed first. Like an injury, we locate and address what the cause is.”

“Even if you are physically healthy, stressors that don’t get addressed and keep piling on can cause a person to be mentally exhausted,” Gallenberg says. “This does not allow our body to perform the way it can.”

All humans have days and periods of time where their mental health isn’t as strong as they’d like it to be. On both good days and bad, proactive mental health care is essential to maximizing performance restoration.” One of the most important proactive mental health care practices is identifying your support system.. If you notice that your mental health is beginning to decline, reaching out for help can get you back to a good spot. Typical treatment for this stage can include counseling or mental health interventions to not only address symptoms, but identify where they are stemming from.

Normal/Average Life Functioning

The middle of the continuum deals with day-to-day issues or tasks that are present. This section includes things such as relationships, friend or family issues/drama, and life transitions.

“Awareness is a key skill across the continuum,” Gallenberg says. “It is especially important when it comes to average life functioning because we can track our internal and external experiences day to day.”

Being aware of what you are experiencing internally and comparing it to what is happening externally is a good way to ground yourself. If you are feeling anxious or frustrated, think about what is happening externally that may be causing you to feel that way. This allows us to reflect on our emotions and reframe our mindset.

Through the ups and downs of average life functioning, it is essential to prioritize proactive healthcare. There are many different ways to maintain your mental wellness. Getting restful sleep, drinking enough water, moving your body, meditating, journaling and practicing gratitude are all great ways to maintain wellness. Doing these things, as well as other activities or things that you enjoy are essential even when your mental health is in a good place.

Your mental health journey is something that should always be a priority because it is a lifelong journey. Once this stage of the continuum is in a good spot, then you have a good base to help reach performance optimization.

Performance Optimization

The far right side of the continuum consists of mental performance strategies and techniques, which inspire peak performance….something all athletes strive for.

“There is a way I can better my best.”

“Top athletes know there is always room to refine or optimize where their peak is,” Gallenberg says. “Athletes who have the desire and the awareness that there is always something that can be done are the ones who continue to grow their mindset.”

Athletes who excel at this space in the continuum have developed a strong base in mental wellness, and can begin to hone in on mental performance tools like focus, imagery, and breathing techniques. These tools combined with strong mental wellness lead to peak performance.

Bottom line, athlete or not, we’re all performers. We are all striving to be our best at something. Whether that is your sport, relationships, jobs, self-improvement, etc. we can all grow.

“Every second of every day you will fall somewhere along the wellness continuum because we all have mental health,” Gallenberg says. “The goal of the continuum is to help individuals gauge where they are at currently.”